Pennies

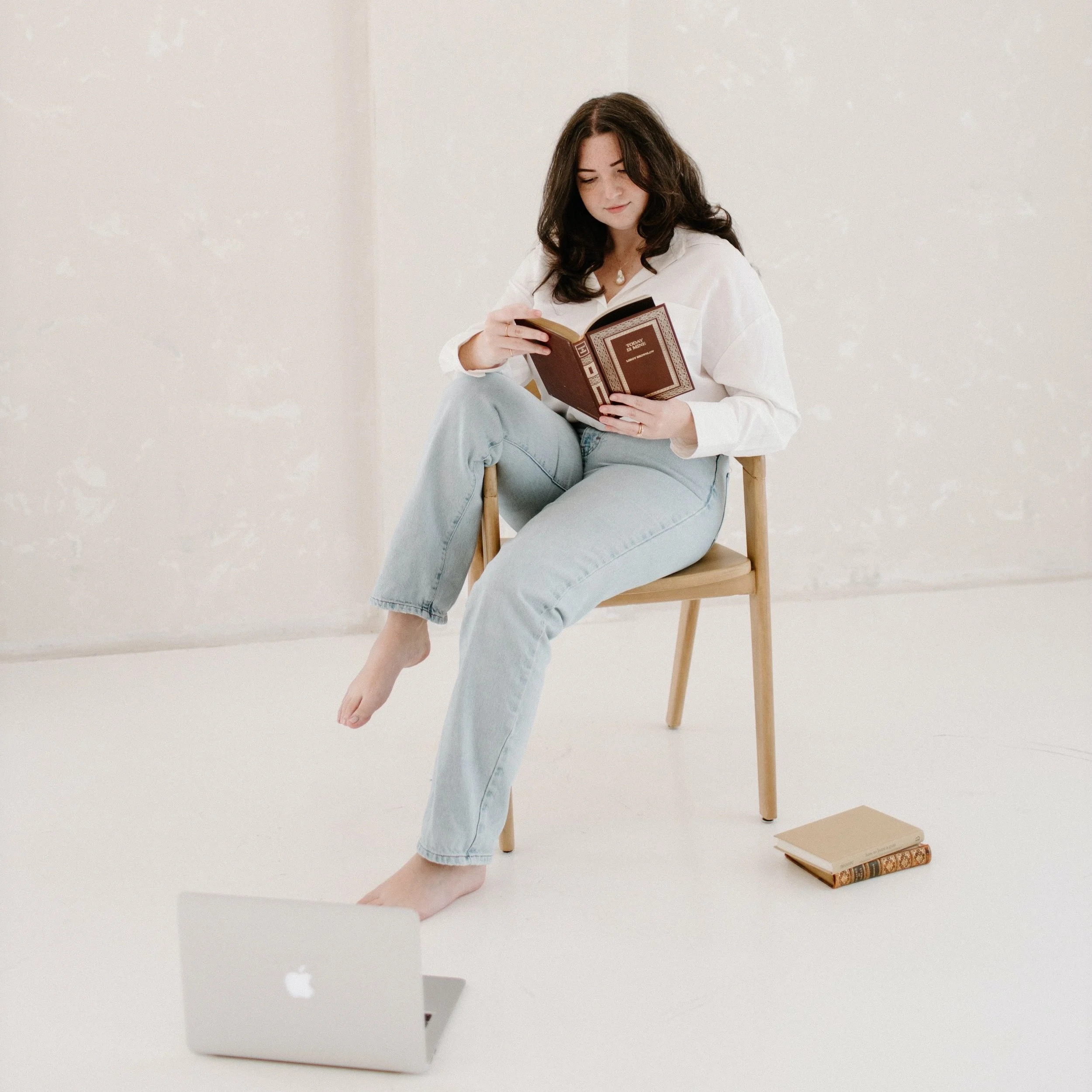

Macy Huston Adams

The cushion extended across

red pickup, rusted in glory.

My legs swung from its elevation,

too short to touch pilled floors.

It moaned as we drove,

each bump lifting me into the air.

We could take on the world—

with brazen perception, we did.

Essential mission at hand:

find a gift for Mom.

I was blissfully unaware of our financial

predicament. Elusive thrift sign summoned.

Limitless possibility racks were stacked:

Snow globes, bike parts, underwear baskets,

faux flowers, sticky candles, held together

by a structurally sound layer of dust and dirt.

Treasure amid gold, young eyes grew wide.

Foot on shelf, reaching to grasp a metallic

set of luxury. Acquired. Accomplished.

Childlike hopping and pleading led to

an early unboxing. Out of the bag,

she pulled three foil disposable baking pans.

Speechless.

I knew they were perfect, her distaste

for cleaning, passion for baking assured me.

Through the wall, through the night,

I listened to her cry.

Macy Huston Adams is a Southern writer based in Oklahoma with roots in Arkansas and Tennessee. Her poetry is greatly inspired by her upbringing with themes of identity and growth. She has a bachelor’s degree in creative writing from the University of Central Oklahoma and is currently pursuing a graduate degree in poetry at Oklahoma State University.

Poetry by Anthony Alegrete

Full Body Exercise

Do __y __ ou know the color of a word’s absence?

_I_ _ c _ ouldn’t tell you, anything about a word’s a-bsence

even when you can’t__t_ discern the word

f-_f rom a shattered syllable know

it is still there, -_I don’t know the color of

an -absence but I do know that when words leave

they leave v_violently, every vowel lay laced

in ra-Azors. Know that some words carry weight and others

carry bAggage. Pronouncing heavy words is just like lifting

heavy objects. You’re aaalways supposed to breathe into the actions

that test your body’s limits, the flexibility of cheek skin is not like

the fleexiblity of muscle fibers. Growing back stiffer

isn’t always s-s-stronger_. S-Sometimes I think my tongue

will fall off from the movement but o-others

I remember, how they tell me the t-ongue

is the body’s strongest muscle.-

Etymology

The words never come when I want them to/ and I guess that’s just a part of our terms and

conditions//I guess these kinds of things are signed with the

tongue//Ineverhadasayinthematter//stuttering never allows for a say in the matter// the halls of school

of my speech therapist were always colder than the halls of my own// when you’re 11 how do you

not take that as a sign of something// that there must be a reason you’re in a public school building

practically alone//something/must be of problem//every speech therapist has a treasure box/just a

thing they do// things feel less like a problem when they're giving you presents/// my last speech

therapist threw two person ice cream “parties”///back then I collected calculators/it just made

sense to unify things//my favorite one was a yellow sun/each ray curved and bounced in silicone

confidence/and it was smooth to the touch//I liked how smooth it was//I don’t remember why

but I remember crying on the way home of my last speech therapist/staring at a park//I think I was

holding the calculator//-and my mother and I might’ve gotten out// and swung on the swing set//

Anthony Alegrete (he/him) is a Japanese American poet and writer born and raised in Western Washington, writing from Orange County, California. He has earned an MFA in Creative Writing from Chapman University’s MFA in Creative Writing Program. His poetry has previously been published in 805 lit+art, The Santa Clara Review, and is forthcoming in The Black Fork Review. @alegrete_writes

Poetry by Adira Al-Hilo

Diaspora

Let me start with a poem about loss.

The way the crooked tree branch watches over me as I sleep

the torn bark

Mimic the lines of my fathers palms

But first, a poem about resent

the way it kept me full on a Sunday night

like hot steam in a Turkish bath house

Now a poem about childhood

That way we can get to the root of the rot

Back and forth now

we have to run back and forth across the fields the only way to catch frogs is to sneak up on them really light so that they don’t hear you

The only way to catch love is to sneak up on it really light so that it doesn’t hear you

Call us in for dinner now

one noise to feed us all

one noise to keep us safe.

Let me tell you a story about loss. But first you have to hold up your fingers. Five children. Three boys and two girls.

A father who holds war in his body.

Let me tell you a story about resentment, you leave your home land and find yourself lost in the pretense of freedom

What is freedom worth without a motherland to look upon

Let me tell you a story about my father. How his eyes sparkle emerald green, how his laugh hits you right here, where your throat closes up

How his call feels like a song to a home you’ve never been to

Let me tell you a story about me. I have no voice. I have no face. I have no country. I am transparent, I float, that’s what I do

I float.

Wild Rabbit

I wait all day for the sun to peak at its favorite spot

I catch the feeling of white light on my eyelids for only a moment

Music plays on the horizon somewhere

a bird cast out of heaven sings home

the anxious neighbor waves

And I wave back

I say hello to the wild rabbit in the grass

I daydream about what it must be like to ride a bike on Sunday without thinking about Monday

I heard somewhere on the news that a body was found in the lake

The sun peaked anyway

We know that the world isn’t what we want it to be

So we continue.

Adira Al-Hilo is an Arab American writer, she has been writing prose and poetry since 2015 and is currently working on her first novel. She has visited over 20 countries, most recently including Portugal where she was a writer in residence. Her work explores the intersection of cultural dialogue, collective consciousness, and writing as a way to frame the human experience.

Instagram: adirahilwa

Susan Alkaitis

Geodes

Above coal beds and glacial lakes,

we wade in the creek today, descending

through viscus masses of bullfrog eggs

sticking to our calves. Aaron says

he’s going to find me a poor man’s diamond

as he clears refugee mussels, digging

into the bank’s loam. It’s futile like it always is

with him, but he says the fertile soil

here means promise of a bounty.

As he bends to examine and discard rocks,

the sweat on his neck reflects just right

against the sunlight so it flashes

for a second and blinds me. Then the brightness

is gone. Of course,

it’s like time. He finds spheres

he declares to be hollow, where pockets

of air, water, minerals could have fused.

He tells me that geodes are native here.

I ask him what he thinks it means to be native

to something, as we watch two frogs,

yellow-throated and male, wrestling aggressively

to defend the silt. Occurring naturally—

meant to be here, he says. See? That’s just it.

I separate layers of shale between my fingers.

We are part air, part water, part mud

and the shale breaks easily in my hands.

Dependence on an unstable foundation,

I know, but today is just today. I want

everything to be simple before I go. I just want

to sit on the edge of the creek for now.

Susan Alkaitis has poems in current or recent issues of the Beloit Poetry Journal, Illuminations, Lakeshore, and Rattle, and recently she won the Causeway Lit Poetry Award. She was also nominated for two Pushcart Prizes in 2024. She is a writer living in Colorado.

Lola Anaya

Autopsy

If you sliced me open and traced

The claw clips of my rib cage

You could snap the plastic between your fingers

And I would reach inside myself

Seeking my ancestral connections

Holding the chambers of my heart together

Soaking my fingers in the pools of blood shared by generations,

Would I feel out of place

Seeking solace within my own body?

Seeking answers from the women who held the women who held me?

Mother pulls my hair behind my face and clips it out of the way so I can eat

I imagine hers did the same

I smell the arroz con habichuelas on the stove bubbling en un caldero

Swallow down scalding rice with the hopes it will block the sensation of uncertainty

The barriers between Mother Tongue and I—

The words are somewhere within me

And maybe you could help me find them

As you whisper sweet Spanish phrases

Into my yearning ears

Break me apart by each bone, I beg,

And fill me with tangible changes

Tasting sure and sweet—

Sticky like the slice of naranja you sneak into my palm

It would ease down my throat

Trying to fill the hollow space in my chest,

Leaving my fingers with the scent of citrus longing for enlightenment

I wish I knew more than the little words I use for you,

mi amor, mi cariño, mi hermoso

I ask how my form is

As I lay there, opened up to you

Your hands grasp at the skin that remains untorn

And you can see that I am trying—

Stitching myself back together

Sticking the plastic shards back in place

Lola Anaya is a Puerto Rican poet from New York City interested in literature and art history. She has been published in Same Faces Collective, mOthertongue (UMass Amherst), Milk Press, and Emulate (Smith College). She has been a featured reader at Spoonbill & Sugartown Bookstore, the 2023 NYC Poetry Festival, and Unnameable Books in Turners Falls.

Mea Andrews

Treading Water

I have seen thighs

synchronize, quadriceps

bathed aqua

tightening, push

release

underwater arabesque,

bathing suits a unit,

uniformity I

never had

at any pool or

beachside. I envy the sharp

point of their

toes and the circles

of their hands, every

movement focused

on treading water

beautifully.

I’ve only juggled

bills, student loans, treaded

my husband, my

mother, the walk

downstairs so quiet

my hands on the wall

to support my weight

to stop the creaking. I’m wrapped

in the iron brown

waters of a river

that has spent its lifetime

eroding mineral deposits,

bare survival of simply

moving forward, no

time for chlorine

cleansing or graceful

sculling. I swim frantic, twice

a month I automatic

deposit, gulp in air

and get pulled back under.

Mea Andrews is a writer from Georgia, who currently resides in Hong Kong. She has just finished her MFA from Lindenwood University and is only recently back on the publication scene. You can find her in Gordon Square Review, Rappahannock Review, Tipton Poetry Journal, Potomac Review, and others. She was a 2022 Pushcart prize nominee, and you can also follow her on Instagram at mea_writes or go to her website at meaandrews.com. She has two chapbooks and poetry collections available for publication, should anyone be interested.

V.A. Bettencourt

Shadow Knitting

She works in shadows cast by an ancient tree

whose rogue roots girdle half its branches and

guide others to sprout strangling shoots.

She knits moths that morph in wind

with the same artistry used by women

who watched trains from windowsills

to transpose timetables into cyphers

they encoded in scarves

scanned by soldiers to win wars.

She purls stitches created by foremothers who

designed sinuous garments in backrooms

centuries before calculus described their curves,

& coded algorithms in fiber

long before Ada Lovelace programmed them

on the first computer

seen as Charles Babbage’s brainchild.

She tailors schemas developed by women who

dodged guilds that blocked petticoats,

patched socks to secure footing

on uneven fields,

bent wooden orders that barred them

& cast off girdles with craft

so she can weave new patterns

to warp the geometry

of stunted structures

bound

by

unraveling

seams.

V. A. Bettencourt writes poetry and short prose. Selected as an International Merit Award winner in the Atlanta Review 2023 International Poetry Competition, her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in The American Journal of Poetry, Chestnut Review, Burningword Literary Journal and SWWIM Every Day, among others. She is a reader at Palette Poetry.

AlYx Chandler

Fingers that Refuse to Core

“Plant peppers when you’re mad or they won’t grow hot” —Journal of American Folklore, also my grandmother

I don’t mean this ugly

but these here peppers aren’t hot enough to run a nose

got no zing

no mad in ‘em

aren’t fiery enough to be in no one’s mouth

on God’s green earth—

you’re safe as can be, hun

eating that jalapeno

never were a pepperhead, were you

still gotta be real careful just cause your mouth

ain’t actually on fire don’t mean your mind

won’t burn your body good

and mean and crisp

ignite it, ya know?

don’t you forget your taste buds

are where you come from

a good pepper like a mad woman

painful as can be

a homemade dish meant to

bring you to tears

let you know what you did

careful when you cut out

what’s hot in a person

you hear me? it’s not always gone

the innards got a way of stayin’

and listen, when you find out what strikes flames

in a person you best move fast

or move aside

hun, stop your crying

it can’t be that hot I been at peace for years.

Alyx Chandler (she/her) is a writer from the South who received her MFA in poetry at the University of Montana, where she was a Richard Hugo Fellow and taught composition and poetry. Her poetry can be found in the Southern Poetry Anthology, Cordella Magazine, Greensboro Review, SWWIM, and elsewhere. Alyx can be found on Instagram @alyxabc, Facebook @Alyx Chandler, and Twitter @AlyxChandler. Her website: alyxchandler.com.

Ann Chinnis

To My Father on My 67th Birthday

I hated your decoys, the red-breasted

merganser, the blue-winged teal,

the northern pintail you jailed

on your bookshelf. I reviled you

as childish for buckling them

into our station wagon

on the opening day of hunting season,

always

on my Halloween birthday.

At bedtime, I loathed you

for softly drying their rubber

and pine, while forgetting to wish me

Happy Birthday. I loved to twist

a ballpoint pen into the red-headed

canvasback’s belly, to biopsy why

you loved it. On my eighth birthday,

I hounded you to take me hunting.

I wanted to carry your dull

Lesser White Whistling.

I wanted you to look up at the sky,

to say it was the blue of my eyes.

I wanted you to put the top down

on the Cadillac convertible

you spray-painted green and concealed

in the cornfield. I wanted to lie down

in the back seat. I wanted you

to cover me with straw. I wanted

to be one of your

decoys.

I didn’t want to slip on the muck.

I didn’t intend to fall in the river

with your lesser white whistling.

I hugged your decoy

as if it were drowning;

like a mother or father, I never let go.

You yelled: Go wait in the station wagon

until I am done huntin’, as I caught

the car keys you threw at me. I was ashamed

to unlock the car. Mom taught me not

to sit on a seat in wet clothes. I refused

to get in and to turn on the heater,

until I could no longer feel

my toes and my fingers. Even now, Dad,

on a cold day, when I hear a car lock

click open, and I inch onto a vinyl seat—

it feels like losing everything.

Ann Chinnis has been an Emergency Physician for 40 years, as well as a healthcare leadership coach, and studies at The Writers Studio Master Class under Philip Schultz. Her poetry has been published in The Speckled Trout Review, Drunk Monkeys, Around the World: Landscapes & Cityscapes, Mocking Owl Roost, Sky Island Journal, Sheila-Na-Gig and Nostos, among others. Her first chapbook “Poppet, My Poppet” was recently published by Finishing Line Press. Ann lives with her wife in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Elinor Clark

The crows returned to the other tree

And I fit my things into cupboards full of other people’s lives,

mismatched mugs, mixed herbs

expired five years ago.

Still, I want to leave my mark, not think of who this room

belonged to before me.

Across the road a crow glares from a rooftop and I wonder

where its tree went. When I was five

I planted a tree in our garden

and called it mine.

That summer, all the trees on our street

were marked for slaughter,

ribbons tied around their waists.

A company said they planted a thousand trees

for every thousand burnt.

But crows plant more trees than us.

I wonder who owns a tree

conceived by accident.

I learn to make my space around the clutter.

I thank the crow.

Outside my flat is a tree.

On my way home, I untie its ribbon.

Place it in the cupboard

for the next owner.

Elinor Clark lives in the North East of England. Her work has appeared in journals including AMBIT, Poetry Ireland, New Welsh Review, The London Magazine and Lighthouse Journal. She is co-editor of Briefly Zine.

Quintin Collins

Self-Care

I place the cup to my lips;

some bourbon escapes

to split the bathwater.

I ran this bath to relax.

I sip this whiskey

because it is expensive

for my salary. I deserve

occasional luxuries

like the organic bath bomb

dissolving blue. Death cares not

for my economics or what softness

I gift my skin, what smoothness

liquor cascades over uvula.

I don’t ponder drowning, God,

or purpose, the crags of existence

I cannot soak away, only the bourbon

wasted in the water. Bath gone cold,

bubbles dissipated, whiskey done,

my nakedness floats with seaweed,

moisturizing oil, flecks of glitter,

but when I rise from the tub,

I don’t shimmer as I had hoped.

Quintin Collins (he/him) is a writer, Solstice MFA assistant director, and a poetry editor for Salamander. His work appears in various publications, and his first poetry collection is The Dandelion Speaks of Survival. His second collection is Claim Tickets for Stolen People, winner of the Charles B. Wheeler Prize. Instagram: @qcollinswriter

Prairie Moon Dalton

Amalgam

I don’t talk to my mother

but when I do she tells me not to

eat canned fish for every meal.

She can practically see

the mercury levels rising

in my bloodstream, molars

and premolars cradled

forever in tin and silver.

I need to change lenses, renew

my registration, salt fruit and wash it

twice, see the dentist and never leave

a water bottle in a hot car. It’s bad

enough, she says, those pins holding

your jaw together won’t ever dissolve,

will be with you longer than I ever can,

will set off every alarm and you’ll have to

say it was you. Worst of all,

when you’re cremated you won’t burn

up, you’ll just melt down.

Prairie Moon Dalton is an Appalachian poet born and raised in Western North Carolina. A 2020 Bucknell fellow and 2022 Neil Postman award winner, her work has appeared in The Adroit Journal, Rattle, Sprung Formal, The Quarter(ly), and elsewhere. Prairie Moon is currently pursuing her MFA at NC State University.

Poetry by Sophie Farthing

Cobbler

In scorched July

beneath trumpet vines

on the bank above the barn road,

we pick blackberries.

We wade knee-deep in poison ivy,

bobbing and weaving between spiderwebs,

sweating through long-sleeved shirts.

My cat stalks smugly through thickets

we can't reach.

The wind drops. The chickens

open parched beaks to pant, horses

stamp at flies, and Queen Anne's Lace

hangs heavy, crowned heads.

We clutch pails still seedy

from April's strawberry-picking.

Our fingers are purple, prickered.

Like elephants, we lift first one leg,

then the other, considering each step.

We call out in whispers, afraid

to wake the wasps.

I can taste the sun as it ripens

the Better Boys and Early Girls up the hill.

I blink away sweat,

and suddenly, a fat hornet

hovers over my hand

raising the fine hairs on my wrist

with the softest kiss of wings.

My heart beats in my neck.

I stand perfectly still.

I do not breathe.

I do not think.

My tongue swells, my mouth

dries out. Empty of sound,

my ears prickle and chill,

and I hate the sweet-sharp tang

of every berry I have ever picked.

I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry

for the things I did. Please

forgive me, and help me to do better,

and please help me to love and serve

you, in Jesus' Name—

The hornet passes over my arms,

clips my shoulder,

hums away.

The earth settles on its haunches.

The crickets take up their old song.

This hornet did not mistake paralysis

for disrespect. This hornet thirsts

for blackberries,

not for fear, but I am too young

to know the difference

when it wears my father's eyes.

I shudder. Ants crawl across my feet.

In the garden on the hill,

a bumblebee careens unkempt

into the heart of a zinnia.

Queenie

I never kissed your full lips. My hands

never wandered. I was sixteen, seventeen,

dazed and confused, watching your breasts swing

as you danced along the stone wall, telling myself

you were ugly. Too much body,

too much woman. Daddy liked thin girls.

I wanted to shrink myself so small

no one could see me standing sideways.

We dreamed chiffon dreams.

In the meadow, home-sewn skirts

tugged over our knees,

we watched the sun fillet the sky

in orange and blue. I held your rough hand,

scholar's shoulders hunched in thrift store cap sleeves,

I gazed into your eyes. We lived like

rabbits in lettuces, lapping each other up with thirsty,

thick tongues. I never kissed your full lips. You gave me

the dolphin beads and the shells,

the lace I never wore. Say it.

Say it! The nest we built us was

too small to settle in. Still I remember my thumb

on the fine skin below your forefinger,

how you cried on my bed against the wall,

how my mother watched me with a strange,

embarrassed face, and how

you pulled your hand away. I'm sorry.

I remember the cricks in our necks.

The one hundred strokes you used to

brush your hair. Stumbling awake before dawn,

bras and toothbrushes and tampons,

molasses in my teeth.

When I surprised you on the landing

at our first meeting, you lifted me and spun me in your arms,

and it had been building in me for a long time,

years and years, but you swung me out of orbit.

My arrows have not flown straight since.

And it never was,

and we never did,

and we never will.

Sophie Farthing (she/her) is a queer writer living in South Carolina. Her work has appeared in outlets including Right Hand Pointing, Beyond Queer Words, Impossible Archetype, and Anti-Heroin Chic. Her poetry is also featured in the horror anthology it always finds me from Querencia Press. She is the 2024 recipient of the Elizabeth Boatwright Coker Fellowship in Poetry from the South Carolina Academy of Authors. Website: http://sophiemfarthing.carrd.co

Lee Fenyes

Inherit

Sooner or later houses will start to

betray you:

the leaky sink,

the suspicious, fuzzy spot on the back wall.

We once had a toilet lift right out of the floor—

the plumbers stared down into the hole,

muttering shit in Greek.

It’s a bit like bodies.

People warn me that I’m getting to that age

as if I haven’t seen already

the catheters and bags of fluid,

and caskets turning friends into earth.

Once you’ve been around,

a lot of things start to look like death, even

a walk in the park or a lunch date.

I can turn most things into tragedies.

My mother tells me,

Just because you think it, doesn’t mean you have to say it.

She also says, You’re haunted,

and it’s true.

My body is an attic full of leftover survival skills:

tense muscles, rapid heartbeat.

My ears swivel at the touch of movement.

I recognize myself in photos older than time:

a birthright of eyes staring out from bone.

As I get older,

memories click into place.

Fogs lift, like the one that had me

panicked in showers, on public buses.

I teach my muscles to soften.

I tattoo myself with branches,

tree limbs reaching across my ribs

instead of sky.

Lee Fenyes studied poetry and English Language & Literature at the University of Michigan, where they received the Emerging Writers Award and the Virginia Voss Award for Academic Writing. Lee's writing, which centers on nature, memory, and identity, has been published in Lavender Review and Ouch! Collective.

Liam H. Flake

tonight the dionysian mysteries percolate from the ceiling of the brothers bar

(or: an ode to self-destruction)

Liam H. Flake is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire and is currently working towards his Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Environment at Iowa State University. His writing frequently ties in both ekphrastic and geographical elements. Flake has previously been published in Meniscus and Gypsophilia. He can be reached at liamflake1@hotmail.com

EliSa A. Garza

How to Become an American Poet

First, understand that poetry

is not for you, little brown girl.

Poetry is written in proper English,

not that border slang you speak.

Second, poems are serious:

love and nature, death,

wars, nation building. You know

nothing of such things, and later,

when you have learned about war,

nations, loved, seen death,

visited nature, you will realize:

your pretty words do not build

our knowledge. If only you

were a man. A man, at least

can see beyond the ordinary.

Third, if you must write,

do not write about women,

or their sphere. Serious poems

ignore domestic life:

no new knowledge in the house.

Fourth, no one will publish

your writing under that name,

so foreign and female. If you

do manage to write in proper English,

seriously, like a man, you must

be anonymous to readers, your name

ordinary, interchangeable, unremembered.

Elisa A. Garza is a poet, editor, and former writing and literature teacher. Her full-length collection, Regalos (Lamar University Literary Press), was a finalist for the National Poetry Series. Her chapbook, Between the Light / entre la claridad (Mouthfeel Press), is now in its second edition. Her poems have recently appeared in Southern Humanities Review, Rogue Agent, and Huizache. Elisa passed away in October 2025, leaving a legacy of poetry, mentorship, and community.

Alexander Gast

Buckshot

i learned to be a man when you blew smoke

in her face and said your glass

was getting close to empty.

when you

bit the head off my barbie—swallowed

it whole and shat platinum blond corn silk

for three days.

men, you taught me,

draw pistols to shoot the breeze. we arm-wrestle

thorn bushes. crunch shrapnel

like big league chew. fuck coors cans

and cum buckshot.

i watched you

wear beehives for sneakers to prove pain

was a fiction of the body. watched you

flip through pictures of your father

and shudder. ran my fingers over the edges

of the hole you punched in the

drywall

/

of the hole you punched in the

cinderblock. saw you chop down a weeping

cherry because crying is weakness.

rip off

your right ear ‘cause you thought it was

the gay one. heard you cry in the shower

after the funeral

/

after the wedding.

Alexander Gast is twenty years old and lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. More of his poems can be found in the Ghost City Review, Shooter Literary Magazine, and crumpled into frustrated balls in his nightstand drawer. His instagram is @alex.gast

Nadaa Hussein

just another war poem

“I refuse to despair because despairing is refusing life. One must keep the faith.” — Aime Cesaire

loss and grief are the most disingenuous words in the English language.

bastardized Indo-European roots

transform and destroy decades

fail to capture a fraction

of the emotional annihilation.

they caused and do cause and will cause

and still.

it does.

what can I say?

the potential seductiveness of language is dangerous[1]

how it eviscerates and self-flagellates,

it’s disgusting, and

I’d bleed to death to write a memorable line.

am I not the quintessential little poet?

take my bones and

make something better out of them.

I can’t keep my faith.

it’s called a war

when it is a slaughter.

what can I say when all that has been, has been torn from me?

say life, and keep the faith

that we will all die in a war over a period and a thimbleful of water?

the bible can be read in a thousand different ways and

there is no neutral, the universal, a farce—

say despair—

I could decimate this language by atom,

can it hold the toll of the rage that lies above the sadness?

the earth still moves.

say, I name it.

there is nothing left.

please.

flex your poetic muscles and feel something true for once.

what was the war poem I wanted to write?

I saw life extinguished, one atom fracturing,

space, it gives. even the air—

it bends—love in

death,

a small mercy.

It’s all terrible.

say life,

one must.

feel something

true.

[1] Bla_K: Essays and Interviews by M. NourbeSe Philip.

Nadaa is a writer, instructor and sometimes barista who focuses on documenting pop-culture, diasporic aesthetics and current socio-political cultural politics with rapid-fire detail and urgency. Her current project is a work-in-progress manuscript, centered on studying and creating multi-disciplinary hybrid and experimental poetry and prose pieces. She attended UC Davis for an MFA in Creative Writing and lives in Northern California.

Ben Hyland

Lunch with the Ex

I’d build her a home if

I were a handy man

with a fat credit limit,

two bed, two bath,

Grand Cayman, North Shore,

where we’d work on our tans forever—

string-bikini old folks

dark as the rocks

supporting our shellacked deck.

I’d go fish, if I could fish, and bring her

blue tang, snapper, sergeant major,

kiss her callused feet even though

I hate feet,

gag at the sight,

but if she walked another day with me,

I wouldn’t care. I’d find her—

Sand-blown dress, flowers in her hair—

and run: A child first sees the ocean.

I’d be honest. If she told me

somewhere on Seven Mile Beach

there were a princess-cut

and she’d lick me all over if I found it,

I wouldn’t just comb,

I’d sift every square inch,

swim out for miles and dive, dive, dive,

come up with nothing, gasping, and be so happy.

Ben Hyland’s poetry is collected in four chapbooks—most recently, Shelter in Place (Moonstone Press, 2022)—and has been featured in multiple publications, including Beloit Poetry Review, Hawai'i-Pacific Review, and Delta Poetry Review. As a career coach, Ben has helped hundreds of jobseekers find employment, even throughout the pandemic. Readers can connect with him and follow his work at www.benhylandlives.com.

Jeron Jennings

Sun enters Aquarius

Jeron Jennings is a poet and social worker; he lives in Missoula, Montana with his partner and their child. His work seeks to explore a space where language loses its utility to create new meaning.

Mickie Kennedy

The Gay Disease

The first time she said it, I flinched

inside, where she couldn’t

see it, not really. She picked at her salad,

while a sour-faced waiter forced more tea

into my already-filled glass.

I wanted to interrupt her, to correct her,

but who was I—a gay son

who took a wife and burrowed inside

a two-story colonial.

Four bedrooms, a bar in the basement.

I could never tell her how much

I missed being touched.

Never share the names of the men

whose slow deaths

I couldn’t bear to watch.

So when she said it,

spearing a crouton with her fork, I let her

say it, lifting my drink—a toast

to my silence.

Mickie Kennedy (he/him) is a gay, neurodivergent writer who resides in Baltimore County, Maryland with his family and a shy cat that lives under his son's bed. A Pushcart Prize nominee, his work has appeared or is forthcoming in Threepenny Review, POETRY, The Southern Review, Gulf Coast, Foglifter, Copper Nickel, and elsewhere. A finalist for the 2023 Pablo Neruda Prize, he earned an MFA from George Mason University. Follow him on Twitter/X @MickiePoet or his website mickiekennedy.com.

Louise Kim

dreaming city

Louise Kim is an undergraduate student at Harvard University. Their Pushcart Prize—and Best of the Net—nominated writing has been published in a number of publications, including Frontier Poetry, Chautauqua Journal, and Panoply Zine. Her debut poetry collection, Wonder is the Word, was published in May 2023. You can find them on Instagram at @loukim0107.

Hilary King

Aftertaste

Maybe it was not the apple

that tempted Adam or even

the bare, brown arm of Eve

extended towards him,

red orb in cupped fingers

that broke Adam’s God-given reserve.

Maybe it was Eve’s mouth,

How it tasted after a bite

of crisp, cold fruit:

like a room newly painted,

a house newly built,

or a garden just before harvest.

He could go there too, Adam

realized, leave this yard with its snakes

and overlords and stench

of rotting fruit and everywhere

dandelions which He swears are edible

but never flood the mouth

with sweetness and promise.

Hilary King was born and raised in Roanoke, Virginia. After spending over twenty years in Atlanta, she moved with her family to the San Francisco Bay Area of California. Her poems have appeared in Ploughshares, TAB, Salamander, MER, Fourth River, SWIMM, and other publications. Also a playwright, she is the author of the book of poems, The Maid’s Car. She lives with her husband, dog, and two cats. She loves hiking and ribbon. Find her at www.hilarykingwriting.com and on Twitter/X at @hrk299.

Jemma Leech

Arriving in a new place is better than departing the old

The day I was born was the day I died for the first time. With no breath inside

Or out, I flatlined my way into the world. Beneath the surface of warm familiarity

Lay cold, bare dread of eternal nothingness. By the time the flat life line warped

Into lively lumpy chaos, the bruise was spreading, the tissue corrupted,

The narrow pathways blocked like days-old milk-straws left in the sun.

By the time I learned to speak, I couldn’t learn to speak. And I learned to walk

From the comfort of my chair. There’s something to be said for it,

I suppose, no ankles sprained on the court or the piste,

No faux pas in polite company, no f-bombs to scare the horses.

No cleats or prom heels, no hikes in bear country or sheer-drop snowy peaks

No sneaking off at midnight to hang out, or shoot up, or send birds flying at cop cars.

No broken wrists or curfews or promises or heart,

Yet much warm praise simply for turning up. Being team mascot, below eye-level,

Not team member and in view, has its benefits too. It’s hard to disappoint someone

If they expect nothing of you. It’s hard to fail, if you make no attempt to win.

It’s hard to take on the world, if the world can’t see you,

Or chooses not to. But, you know, the sun still shines and the flowers

Still smell, and the rivers still tumble over rocks and sand. The red kites still spin

And the painted dogs still croon to the mosaic of the harvest moon.

The horizon lies flat and distant. I was there, once upon a time,

On the day I died for the first time.

But not today. Today, I’m still here.

Jemma Leech is a silent poet with a loud voice. She is a British/Texan poet and essayist who lives in Houston. While she speaks from the perspective of someone with cerebral palsy and a wheelchair user, she also celebrates nature, reflects on history, and observes the intimacy of human relationships. Her work has appeared in the Gulf Coast Literary Journal, the Houston Chronicle, The Times, the Times Educational Supplement, and on ABC News. She has given readings of her work through Inprint, the Houston Public Library, and Public Poetry Houston. www.jemmaleech.com

Carlos Martin

I Did What a Child Does

After Li-Young Lee

So that she could take a job,

after my father left with the waitress,

my mother teaches me to cook us dinner.

1. Chop the onions finely,

they will muddle into the sauce.

The pressure cooker’s explosive

reputation terrifies me.

She teases, nothing but a rumor.

2. Bathe it in cold water.

3. The sound of steam is a warning.

I ask about my father.

The sound of steam is a warning.

Beware, a meal can become a curse tablet.

4. You must first fry and brown the beef in olive oil

to give it color.

She dances from stove to sink to steak,

she’s always dancing.

She dances like we’re not clinging to the

walls of that small townhouse kitchen,

the survivors of our shipwrecked family.

5. Take the beef out and fry the sofrito.

The frying onions excuse

the release of suppressed tears.

A meal can be a curse tablet.

We eat in silence.

My daughter giggles when I mimic the percussive pressure cooker.

shique-shique-shique-shique-shique-shique-shique

She repeats:

1. Simmer rice 15 minutes, steam rice 15 more.

I ask her how we chop the onions.

2. Chop them small, Papa.

My daughter Elena never met her namesake

Maria Elena Sanchez,

gone to glory before Elena was born.

She eats the stew we made,

her grandmother’s gift to us.

She laughs and she says,

Papa, you’re dancing.

Carlos Francisco Martin is a graduate student in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Florida International University. His poems can be found in the South Florida Poetry Journal and were selected at O Miami's Underline Urban Haiku contest. Carlos lives with his wife and two daughters in Miami, Florida where he is a practicing lawyer.

Akash MattupalLi

Shootings in America

We were talking about Death at the dinner table,

lightning and the stormy thunder buzzing faintly outside.

I was eating their zucchini bread with spread butter,

“Did you know that you could buy guns at Walmart?”

I thought I heard their dog whine behind us.

I was a military recruit when I first shot an assault rifle,

bullets in the magazine clanging like bells in Hindu temples,

I took in a deep breath and looked through the scope.

The target was moving, I was calm as a feather,

I pressed the trigger and the recoil nudged my shoulder.

I had hit the target, I became a marksman.

Why would they ever put guns in the hands of teenagers?

My friends told me of their suburban American schools,

the active school shooting drills they had to do,

hidden in corners of classrooms in the dark,

under chairs or tables, becoming roly-poly bugs.

“Does this happen in other countries?” one of them asked

me, my fear in middle school was about not fitting in,

not about being shot.

Mother says she’s terrified of going outside on her own.

“These crazy idiots with guns, they’ll shoot you,”

at times, it seems more likely to end up in a car crash

on Beltway 8, Houston’s reputation for bad drivers

being louder than the Lone Star Flag.

In this odd game of Russian roulette

do people bleed in Red, White, and Blue?

Terms like filibusters or caucuses or clotures or recesses

are thrown around as the shell casings of bullets fall.

The only time a white supremacist used the metric system

was before they squeezed the trigger.

Currently working in semiconductors with a mechanical engineering background, Akash started to write at 15 to understand his identity. Now living in the US, he has also lived in India, Singapore, England, Saudi Arabia, and Spain. Through his work, he hopes to reflect on the intersection of the immigrant Indian identity and the environments that he has lived in.

Joan Mazza

Blue Zones Fare

Call me gullible again. I fell for the claims

of longevity with health, bought the pricey book

with stunning photos of foods I never heard of,

went on to buy miso, dashi, seaweed, and tofu,

watched the YouTube videos on how to prepare

and store them. This book is nearly vegan

with portions sized for petite five-year-olds.

No fish or shellfish, not even for Sardinia

and Okinawa, where the sea offers its buffet.

Listen, I hate to confess how easily I’ve been

bamboozled by pretty pictures and promises

that I might live to 100, remain vibrant.

Let’s face it, I’m not climbing up and down

the mountainside with a sack of turnips

or digging potatoes with only hand tools.

I never have and never will. It’s too late

to grow muscular and athletic at seventy-two.

But please, don’t lie to me about ingredients.

Don’t sell me books with untested recipes

whose baking times and quantities are out

of whack. Don’t tell me I need to buy

breadfruit, chan seeds, mirin, purple sweet

potatoes, and one large, hairy tiquisque.

The joke’s on me. I’m still a mark for magic.

Joan Mazza worked as a medical microbiologist, psychotherapist, and taught workshops nationally on understanding dreams and nightmares. She is the author of six books, including Dreaming Your Real Self (Penguin/Putnam), and her work has appeared in Atlanta Review, Italian Americana, The Comstock Review, Poet Lore, Prairie Schooner, Slant, and The Nation. She lives in rural central Virginia.

Poetry by Chimmy Meer

“Imagine if this was another country, not nowhere,”

not weaving, not crisis,

not defiled, not child

in house desert,

not dreamlike

not found

truth: your skirt

of fate, your thigh,

a faithless touch

incurring scar

I am afraid to lay

on you the weight

of my own

hand.

“I have a past. But I am here.”

Said my mother once, folding her sadness

Into a tight bun. She hung the photos of her grandparents

Courting in Intramuros, a cochero and Spanish maiden, Indio and salvaged.

How did I get here? Skirt lifted to the knees, ankles crossing

Clear shallow water. I woke on another island

Making music out of violent silence

The dogs hated my arrival, though they cowered and

Lowered their eyes—they thought I was just as broken

Framed and forgotten once I married

Or perhaps reborn? As survived and justified—

Ferried from a set of perils where finally, I am

Muttered into the light, seen plainly for who I am

Languageless and safe: why do I imagine another country? my country

As another? This imagined, dreamlike country

Exists only in my head.

I made you write it down.

Why you left: bored of the task that is upon

Everyone: to escape the poverty of their lives.

To abandon word and tradition, the slow climb

Of generations toward some kind of meaning.

In reality, breaking back to eat supper. Watch:

No one ever truly knew what was up with the

Final supper, it was another image we have let

Organize our lives. Your mother saying, so what?

If we only knew ourselves mirrored in religious figures

At once archaic and real. You will not do it anyway

What was entrusted to you by the family, to wash

The feet of the common folk.

Chimmy Meer is Filipina poet and filmmaker who lives in a sleepy town called Marikina with her spouse and two pets. She teaches high school creative writing. She has a BA in Film and an MA in Creative Writing from the University of the Philippines.

Patricia Heisser métoyer

lift every voice

patricia a. heisser métoyer is completing an International MFA in creative writing and holds a PhD in Clinical Psychology. She is an award-winning essayist and recipient of The Los Angeles Review of Books Publishing Fellowship and The American Film Institute Fellowship. She is a Ms. Magazine Feminist Scholar. patricia has published writing on multiple platforms. She is currently seeking representation for her first book of cross-genre narrative fiction and nonfiction on African American and African Diaspora Literature and Art. She is a member of the Author’s Guild, the American Psychological Association.

Madison Newman

The Third Dead Orchid

I called my mother to tell her

I tried to rescue another one of you

from the neglectful cold of the grocery store,

but you are dead

again

I buried you in a shoebox

in the backyard like a dead pet,

packing the corners with scraps of satin pillowcase

and fertilizer, your pot a hospice

and a refusal

from the time I unwrapped you from the stained cellophane

I strung your stem spine up with little white pearls,

made you offerings of eggshells

and ice cubes in vain attempts at revival.

It is my fault

for believing I can always play savior.

Your quick descent lasted only two and a half weeks—

two and a half weeks of your cloud-purple heads raised

in prayer, then your color fading like that prayer

Unanswered. Your stem drooped down

like an old woman’s brow,

roots sickling

and pressing their gnarled and tired mouths

to the moist soil.

Finally,

the end

was a self-guillotining:

your withered heads

. rolling away

Madison Newman (she/her) is a student, grant writer, and lover of words. When not writing, she enjoys reading, cooking, spending time with her cat, and caring for a copious amount of houseplants.

Molly O’Dell

At the Buffet

Her royal blue blouse shimmies

in a shaft of light

while she talks with her husband

who throws back his head to laugh.

Her hands shake symmetrically,

uncontrollably. Left hand holds her plate

while the right one scoops pickled

beets then lifts the top off the stewpot.

As they sit and talk I watch

her eat her soup. Each spoonful’s

kinetically delivered with a quivery

hand that spills more soup

as the tremor’s rate and range

increases the closer the spoon

moves towards her mouth. The thing is,

she never winces or whines

and her husband doesn’t take his eyes

off hers, try to help or say he’s sorry.

Molly lives in southwest Virginia and loves being outdoors. She received an MFA from University of Nebraska and her published collections include Off the Chart, a chapbook, Care is A Four Letter Verb, a multi-genre collection and Unsolicited: 96 Saws and Quips from the Wake of the Pandemic, written for her public health colleagues and anyone else tired of SARS Co-V2. Molly can be found online on Instagram @mollyodell1787, Facebook @Molly O’Dell, and her website www.doctormolly.net.

LeeAnn Olivier

Bright Star

When the anesthesia wanes I claw through cuffed

wrists, my glutted throat a moat of gravel, tubes

sprawling from my veins like the roots of a black

gum tree until I’m pulled back under, and I take a night

train to a half-world half a world away, a serenade

of cyanide on the bedside, a red star carved at the edge

of the Black Sea. The whittled rattle of spokes on tracks,

maps and gestures little reliquaries, a stranger’s mouth

on mine, an utter hush washed over us as the lacquered

leaves of her eyes gleam greengold and my pulse rustles

like a hiss of waves. I’m dreaming my liver donor’s

dreams. What lags behind flickers and hums, his

mythologies nestled deep as a swell of bees in my ribs.

Raised in Louisiana on new-wave music, horror films, and Grimm fairy tales, LeeAnn Olivier is a neo-Southern Gothic poet and writing professor. Her poetry has appeared in dozens of journals, including The Missouri Review, NOVUS, and Exposed Brick Lit. As a survivor of domestic violence, breast cancer, and an emergency liver transplant, Olivier hopes to help her students navigate their traumas through creative expression.

Dominique Parris

A Part

Some things know about letting go

about how and when,

and how much.

My knife rocks around the circumference of an avocado pit

and two halves cleave with ease—

though that’s not the wonder of it.

Slicing the length into quarters

reveals twin bruises, grey and sunken.

No matter.

I coax the stippled peel backwards, yielding

whorls of purple velvet underbelly,

I watch the flesh of the fruit

as she relinquishes her blemish

to the retracting peel—

jagged half moon

perfectly excised.

Another clean leaving.

Dominique Parris (she/her) is a poet and social justice practitioner. She holds a Masters of Education from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and a Bachelor's degree from Wellesley College. Originally from the suburbs of Philadelphia. She is a queer, multi-racial, mother of three living with her spouse and children in Washington, DC. www.linkedin.com/in/dominiqueparris/

Bleah Patterson

I don’t know if I’ve ever been in love or if I just love the beginning and end of something

Bleah Patterson (she/her) is a southern, queer writer born in Texas. She has been a SAFTA and BAC resident, and her various genres of work are featured or forthcoming in Barely South, Write or Die, Phoebe Literature, Milk Press, Beaver Magazine, Across the Margins, Electric Literature, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and elsewhere.

Poetry by Tina Posner

All I wanted were white go-go boots

to wear with my purple, crushed-velvet skirt

that laced up the front with a thin chain.

I was in love with the frugging teens

in Pop-Pop’s brief paint-by-numbers art.

The deep blue walls and blue carpet gave

my room an undersea hue, and I’d float

on my bedspread–a floral riot of violet

and red—daydreaming of girlfriends

who’d be more like sisters, teaching

me dance moves for boy-girl parties.

I’d unhinge the laminate desktop and

write out invitations, lift the heavy lid

of the vanity to reveal cheap jewelry,

bright shadows, and bubblegum gloss.

This is my future, I’d whisper to prints

of sad-eyed girls with sad-eyed cats,

listening to my heartthrob name new

feelings on my close-and-play.

Pot of Fire

Buffalo lake-effect snow dumped

a frozen flood waist-high. Sidewalk

glaciers refusing to recede until

long after spring break. Cold, dark

months puddled, warping the inlaid

parquet floors, soaking our socks,

and leaving chalk outlines of salt.

Looking for ways to kill time, one of us

suggested we make chicken wings.

Not me. I couldn’t imagine anything

more redundant than the town’s trademark

served in every restaurant, every bar.

And the bars were only outnumbered

by the churches. But half-crazed with

sky-gray boredom and bong hits,

we couldn’t agree on anything else.

Wings, flour, spices, all ready to fry.

But the oil in the pot combusted.

We saw the smoke, the fire, and froze.

I don’t know who broke the spell

first. Maybe it was VB, ever precise,

who noted the unsafe absence

of an extinguisher. Maybe it was K,

sober and shy, who pointed out

the obvious: It was a grease fire.

Since our pots had no lids, K soaked

a washcloth we kept in the kitchen

as a potholder. The fire swallowed it

whole. With only a shaker full of salt

to sprinkle, I improvised with flour.

The grateful flames whooshed

to the ceiling. VB noted accurately,

ex post facto, that flour is flammable.

Then the one we called Momma,

for her size, yelled that the gas stove

would blow, so we fled the kitchen,

waddling into the street, single-file

on a thin path carved in waist-high snow,

just as we were, in slippers, jacketless.

I half-dug and half-swam in a panic

to the neighbors’ door, my frozen fists

pounding, Call 911—big fire!!!

The orange dance in the windows

suggested utter destruction within.

VB, near tears, mourned her new

contact lenses, Momma her books,

me my poems. I don’t know what

K mourned—she never said.

Four fire trucks whined to the curb.

Brave souls in their fireproof gear

who dared to enter our humble inferno.

Then from out of the hot maw flew

the smoldering pot. Here’s your fire,

ladies, a gloved finger pointing

as it sank, hissing in the snow like

a witch undone by water. I argued

to keep the charred pot on the lawn—

its stink an ever-funny punchline;

like laughter trapped in amber.

I wonder if they ever tell this story

to their friends. I wonder why we,

once so close, drifted like snow.

My past is full of such numb spots,

and I can’t recall any reasons.

With no one to ask, I’ll never know

what happened to those raw wings.

Tina Posner has published poems in Ocean State Review, EcoTheo Review, Autofocus, Switchgrass Review, Ashes to Stardust (Sybaritic Press, 2023), and Resist Much, Obey Little (Spuyten Duyvil, 2017). She has published over a dozen books of nonfiction and poetry for classroom use. An NYC expat, she lives in Austin, TX.

Elisabeth Preston-Hsu

In Songkhla, Thailand

Do not sleep towards the west, a Thai friend said.

The dead face that direction. It’s bad luck.

I looked everywhere but west that year, for a lottery ticket,

a comfortable pair of jeans, for an avocado perfectly

ripened. I found nothing. I never knew which direction

I faced when asleep in Thailand. Where my nightmares

found the dead walking through me, above me, next

to you, restless. Mudslides striped the north after days

of rain in December. So many pieces carried to washout and slip

in the south. Chickens suffocated by mud in the east. Cinder blocks

scraped wounds into the hills. But these were not the bad luck.

It was that I did not look west to you, and reach. A coolness

in all that rain’s potential. Next day’s morning on the beach,

ghost crabs scurried west, sun pulled forward by claws

and shadows. Unraveled the air, snipped the breeze, carried

the night's heaviness away. An attempt in a year so small

it felt like half a breath. A breath so short, I forgot how hard

the rain had hurt. How I pooled at the hill’s base and found

a gentle shoreline, its lip of waves closing the wound.

Find Elisabeth Preston-Hsu’s work in the Bellevue Literary Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, CALYX, The Sun, MacQueen’s Quinterly, North American Review, and elsewhere. She’s a physician in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Instagram @writers.eatery.

Poetry by J.B. Rouse

Of Territories & Offenses: 1869

IN CASTORS AND CHINCHILLAS

a few Christian men have accomplished wonders

orderly and law-biding

THE SCIENCE OF LIFE mere canvas

But Among these savages

squalid poverty knavish remnants

fearful shrieks of the hopeless heathen

From the Episcopal chapel

OXY-HYDROGEN LIGHT

cheerful and prosperous

horses and wagons, coats and trousers

SILK FACINGS AND VELVET COLLARS

Of Territories & Offenses: 1975

SLASHER MURDER EAR TO EAR

AMERICA’S PRIZE PACKAGE

100,000 pounds of federal meat

Armed with rifles and shotguns

3:00 THE ASCENT OF MAN

tear gas canisters about 8:45

a curfew declared

10:30 LOVE OF LIFE

hammered out all-night

to prevent it from spoiling

Of Territories & Offenses: 1988

PLEASE ACCEPT OUR SINCERE

THANKS FOR GIVING

so-called peace pipes

(Your) EVAPORATIVE FRATERNAL BENEFITS

(They say) The great deity could commune through smoke

warclub bric-a-brac

EASY-TO-MAINTAIN AND EASY-TO-LOVE

I’m seeing the sacred at rummage sales

Dr. Jeremy Rouse is an educator, musician, and writer currently living in Washington state. His creative output includes albums, zines, short fiction, and poetry, often featuring found poems. Much of Rouse's work is informed by his Yankton Sioux identity. Often utilizing abstract language and imagery, he hopes to invite audiences into a collaborative journey of interpretation and meaning-making.

Roscoe Saunders

Tetris and Questions of Infinity

Oh, Tetromino, can we spin a while longer?

This lemniscate dance is dangerous, I know,

but slipping on ice is far preferable

to whatever awaits above.

I am set at ease by your presence, so please,

tell me: is there an indefinite strategy?

We grow closer to the tetrion ceiling,

the gaps we left below so out of reach––

and the skewed pieces grow engulfing in their tide.

I no longer ask if we can spin forever,

because this is no way to live, back against the wall.

But hold on to me, please. I’m afraid of topping out.

Tetromino, tell me there is beauty in the end,

like four lines flitting into nonexistence,

a meteoric straight piece at its side.

I’m full of fear that the Overbalanced Wheel won’t turn,

or the monkey won’t typewrite Macbeth word for word,

or the sun will explode, if bombs don’t end things first.

Tetris, give me clarity, focus, the time to set things

in the right place. I’ve dug myself out of holes before,

filled the gaps I needed to, but I’ve never avoided the end,

never escaped a malexecuted T-spin or a misplaced piece.

Tetromino, nobody can do the impossible, right?

Roscoe Saunders is an emerging, neurodivergent poet, born and raised in St. Augustine, Florida. He graduated from Flagler College in 2024. He is a lover of video games, tabletop roleplaying games, and the stories that are told in both mediums. He finds inspiration in often unexpected topics, but tends towards the concepts of place, environmental issues, and identity.

Sameen Shakya

The Sewer Rat

We rain dogs huddle together

under the awning of some bar door

passing around a single cigarette

among the five of us and my eyes dart,

at L, who lights and takes the first puff,

singing compliments about this girl he met

yesterday at some library, god knows

he’s got clean enough clothes that they won’t throw him out.

She was reading a book on chemistry, and he

asked if she could see some between them.

It worked. M laughs the first and I eye

as the cigarette passes to his lips. A says,

“Well, is there?” and they all laugh. I just

want the goddamn cigarette passed to me.

O asks me when did I last eat. “You’ve got

this look on your eyes” as A takes his puff.

The seconds pass without a sense of urgency.

Finally, it gets to O then me. I can taste it.

The smoke filling my lungs. I’m gonna savor it, but

as O passes the dying cigarette to me

the rain fueled wind blows it away,

and it lands on a puddle to be bulleted by rain.

They stand silent as I walk off.

O calls for me but my hoodie drowns him out.

I slink into an alley as a rat in a sewer

to be drowned. Maybe I will too.

I just wanted a goddamn cigarette.

Sameen Shakya’s poems have been published in Alternate Route, Cosmic Daffodil, Hearth and Coffin, Roi Faineant and Thin Veil Press, to name a few. Born and raised in Kathmandu, Nepal, he moved to the USA in 2015 to pursue writing. He earned an Undergraduate Degree in Creative Writing from St Cloud State University and traveled the country for a couple of years to gain a more informal education. He returned to Kathmandu in 2022 and is currently based there.

Bethany Tap

“Life lies not in what is inherited”

from Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics

Bethany Tap (she/her) is a queer writer living in Grand Rapids, Michigan with her wife and four kids. Her work has been published in Emerge Literary Journal, Third Wednesday, and Yellow Arrow Journal, among others. You can find more of her work at bethanytap.com, Facebook @bethany.tap, and Instagram @bjtaP.

Emma Wynn

At the Jewish Deli

Bowls of pickled vegetables in every booth

not just cucumbers but green tomatoes

like hunks of jade, the bone china vases

of pearl onions and rinds of humble cabbage

flecked with dill, sometimes even a beet

trailing pink plasma like a star

that’s how you know this is no tourist trap

this bowl of mysteries

Papa Joe with his rabbi’s beard

forking out whole cloves of garlic

for my father and me

our eyebrows thick, noses majestic

as the prows of ocean liners crossing the Atlantic

from Romania to Brooklyn

how aching the flood behind my teeth

as it rises dripping from the brine

the translucent fruit of some far garden

thrown scalded into the tight darkness

to be made this sharp, this nourishing

as imperishable as we are

Emma Wynn (they/them) teaches Philosophy, LGBTQI+ U.S. History, and Psychology at a boarding high school in CT. They have been published in multiple magazines and journals and nominated for the Pushcart Prize twice. Their first full-length book, “The World is Our Anchor,” was published in 2023 by FutureCycle Press. You can find more of their work at emmawynnpoetry.com and on Instagram at #ewynnpoet.

Ellen Roberts Young

Those Who Stayed

Santa Clara Valley, California

Everywhere else peaches are sold

unripe, apricots are inedible.

Aunts and uncles sit on the porch

and remember prunes. The orchards

have filled with houses: this is old news.

The aunts and uncles are old

and keep retelling the way

they used to go up to the City.

Their young have packed and gone

to other cities not worthy

to be called the City. The old folks

read the papers and lose their

passwords. The young are out

of reach, waiting for rides

to some ash grove where they hope

to find “inspiration.” The uncles

and aunts remember that longing.

They dared not yield to it

when prune orchards filled

the valley and paid the bills.