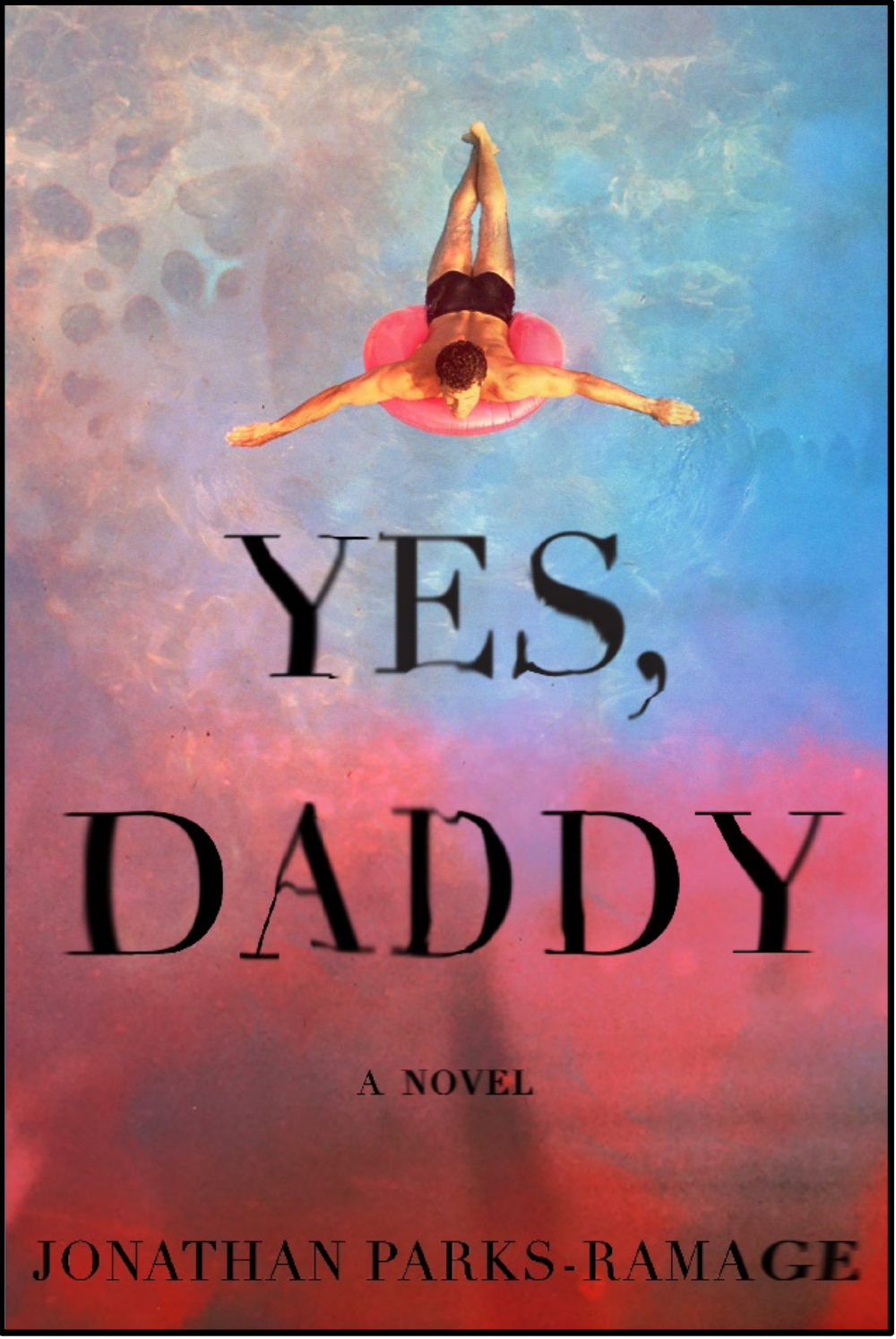

Jonathan Parks-Ramage: "Yes, Daddy" (Fiction)

“What does one wear to a rape testimony?” Jonah Keller asks on the first page of Jonathan Parks-Ramage’s debut novel, Yes, Daddy (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). “Nothing too tight, nothing too baggy, nothing too ratty, nothing too expensive … nothing flamboyant, nothing too gay, nothing that might trigger juror prejudice.” Getting hung up on sartorial details in the face of something so deadly serious seems like the darkest of comedies, but it reveals the very unfunny irony of such judgments, whether in the courtroom or in public opinion. Jonah knows that verdicts and sentences often hang on the length of a hem line or the angle of a plunging neck line. “Something to wear while the world decided if I had been raped,” he muses.

The seam between devastation and wit runs through Parks-Ramage’s whole novel. It is the art of blurring the traumatic and the trivial that is at the heart of sophistication, the native aesthetic of many gay communities, including the cadre of New York City queens who populate the novel’s pages.

The story follows the ambitious and dangerous rise of aspiring writer and itinerant waiter Jonah Keller, who has fled a devastated Evangelical family and compulsory ex-gay therapy. The linchpin in his plan of ascent is Richard Shriver, an older, established, wealthy writer (and titular Daddy), who will feel familiar to readers of Christopher Castellani’s portrayal of Tennessee Williams in Leading Men. Jonah’s plan to ensnare Richard for his own enrichment is calculating and succeeds almost too well, landing Jonah in Richard’s debt from the beginning. As their relationship grows, so do its twists and the number of people who share their trysts out at Richard’s country compound. Behind its walls, Jonah meets the other older residents, as well as the chiseled young men who wait on them. But underneath the booze and the braggadocio and the biceps, a secret holds the little society together—a secret that wraps its tendrils around Jonah’s heart before he realizes that he is the one in the snare. In the harrowing final act, Jonah must decide how to extricate himself from the cycles of lies and abuse that have dogged him his whole life.

After I finished reading it, Yes, Daddy swirled in my psyche for days as the emotional layers worked themselves out. I felt like I had read a gay retelling of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Though Parks-Ramage’s novel is not episodic, it carries a similar aura of unreality, especially as its individual moments are juxtaposed against one another. There is the world of Richard’s opulence and abuse, the world of Jonah’s professional recovery, and the world of his Evangelical reprise. But perhaps the salient difference lies not in those worlds, but in who Jonah becomes in each of them. He is a shape-shifter, conforming to various milieux and their rules for survival and advancement. As such, Jonah comes across as a hollowed-out character, lacking a core or a center. There were moments in reading when I felt frustrated with his total lack of agency or his almost willful susceptibility to gaslighting. But I suppose I should have expected this from a character who, in the first few pages, takes the witness stand and reverses his position, denying his abuse and protecting his abuser. He is a man in search of a story he can live with, and he is not above rewriting his story to make it more livable.

It is exactly the kind of rewriting that goes on under the guise of so-called ex-gay therapy, conversion therapy, reparative therapy, or sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE)—the careful revising of relationships, motives, and identity, in which the “client” is encouraged to embrace a lie about their identity and their desires. It is a scheme in which queer people are lied to until they become liars, spinning false identities and denying their true ones until they don’t know who they are; they only know who they are expected to be.

Perhaps it is not only the SOCE survivors who know something of this duplicitous adaptation. But Parks-Ramage’s choice to pair the Evangelical ex-gay abuse that Jonah suffers as an adolescent with the physical and sexual abuse he endures as an adult invites the comparison. The two are obviously not the same for innumerable significant reasons. But perhaps the two are offered as foils, a way of understanding one by the other, or vice-versa.

How, we might imagine Jonah’s midwestern mother demanding, how could anyone, let alone my son, subject himself to such horrific treatment?

How indeed? Richard Shriver might reply.

How indeed?

—Jonathan Freeman-Coppadge

Fiction Editor

JONATHAN PARKS-RAMAGE’s writing has been widely published in such outlets as Vice, Slate, Out, W, Atlas Obscura, Broadly, and Elle. He is an alumnus of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Parks-Ramage lives in Los Angeles with his partner, Ryan O’Connell. YES, DADDY is his debut novel.